Say goodbye to writer's block AI

Intelligent Writing Assistant

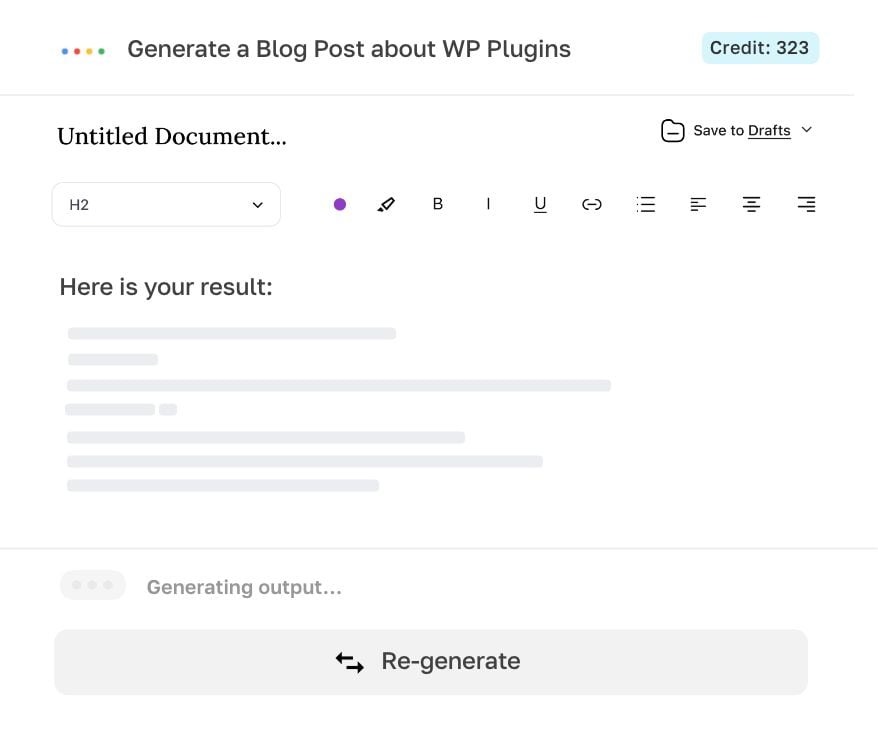

Writer is designed to help you generate high-quality texts instantly, without breaking a sweat. With our intuitive interface and powerful features, you can easily edit, export, or publish your AI-generated result.

Generate, edit, export.

Powered by OpenAI.