Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Experts believe that the project was launched in China and depends on the download system. “It appears to be a lender that is selling illegal or illegal content,” said Zach Edwards, senior cybersecurity researcher at Silent Push, which specializes in the cyber ecosystem.

Often, Edwards explains, dropshippers wait for a customer to place an order, then buy the item from a cheaper online retailer, repackage it, and ship it to the customer. Edwards says a network operator can create hundreds of pages, use a few ads for products, and rotate Facebook pages to promote their products. “Even when some sites or ads are caught and taken down, others continue,” says Edwards. “It’s a spray and pray method.”

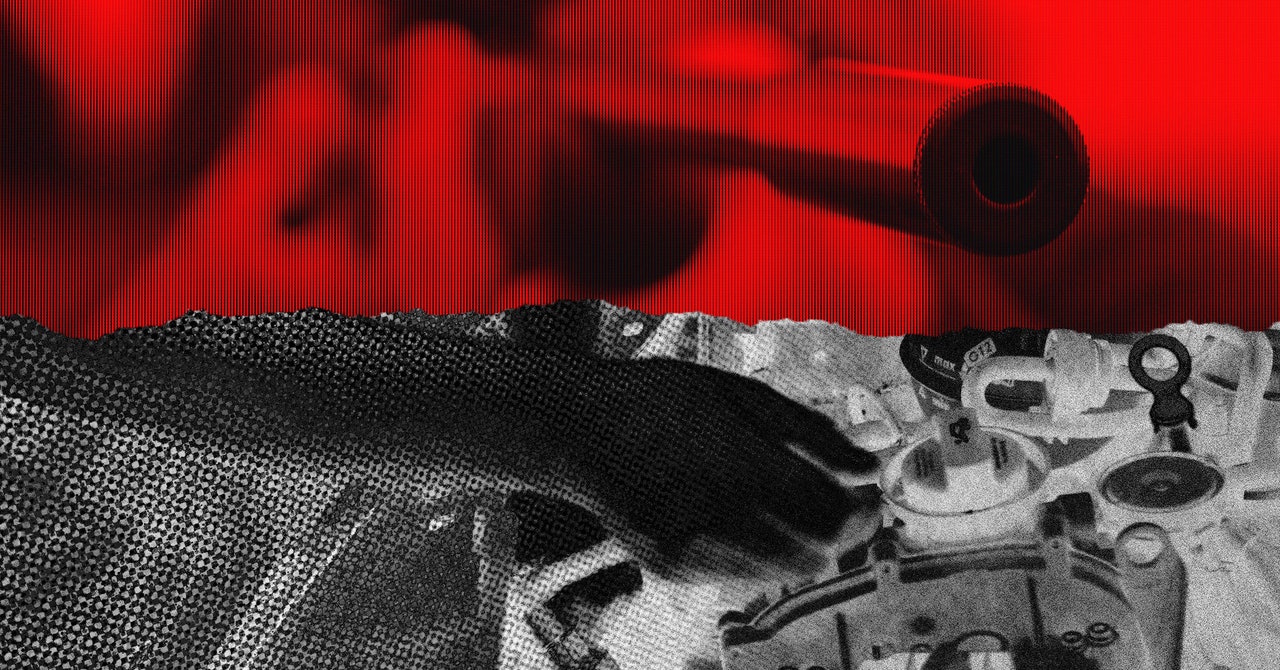

Meta strictly prohibits advertisements for tools, blockers, and other modifications. According to Meta, ads are reviewed by automated systems with the help of human moderators. However, enforcement has been inconsistent: While at least 74 of the ads we investigated were removed for violating the platforms’ policies, the rest appear to have been successful.

When WIRED reached out to Meta, the company said it had removed the ads and associated advertising accounts. However, a quick search of Meta’s Ad Library revealed that almost exactly the same thing has been published.

“Malicious actors are constantly changing their tactics to avoid enforcement, which is why we continue to use tools and technology to help detect and remove illegal content,” Meta spokesman Daniel Roberts wrote in a statement.

Roberts says many of the ads WIRED never ran, meaning few people ever saw them. However, at least two ads reviewed by WIRED had thousands of comments, including accusations of ATF honey, complaints from self-identified buyers whose items never arrived, and testimonials from others who said the product worked as advertised. WIRED reached out to several commenters who said they bought the product — none responded.

The ad has also attracted officials from the US Department of Defense. An internal briefing to Pentagon employees, seen by WIRED, says that advertisements for oil filters were sent to US military personnel on government computers at the Pentagon. The story, which the source said was given to senior officials, including the head of the US Army, raised flags about how social media algorithms are being used to target the public.

Meta’s Ad library provides little transparency, leaving it unclear how these ads are created. Researchers suggest that Meta’s powerful marketing tools, which allow advertisers to target audiences using targeted methods, could be used to reach gun enthusiasts or the military. Although Roberts confirmed that Meta didn’t realize the ads were targeting the military, WIRED found that advertisers could target users who listed their job titles as “US Army” or “military” in their profiles — an audience Meta estimates include. up to 46,134 people.

Meta platforms have long struggled to stop the sale of guns and other items. Tech Transparency Project’s October 2024 joint report found that more than 230 ads for guns and magic guns were posted on Facebook and Instagram in about three months. Many of these ads direct consumers to other platforms such as Telegram to complete transactions. In 2024, two men from Los Angeles County was accused of running an “unlicensed gun business” that used Instagram accounts to advertise and sell more than 60 weapons, including guns and weapons with unnumbered serial numbers. All these people pleaded guilty.

Silencers are rarely used in criminal cases, but their use is increasing – almost 5 million registered in the United States, up from 1.3 million in 2017. Last month, Luigi Mangione, a 26-year-old software developer reportedly used a 3D printed gun with a silencer to shoot UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in a midtown Manhattan street.